The History of Money and Currency in the United States: From Gold to Fiat Faith

Money is a story of power, trust, and necessity. In the United States, that story began with colonial barter systems and Spanish coins and evolved into a global reserve currency backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Along the way, financial crises, wars, and economic shifts reshaped how Americans think about money, leading from gold and silver to the modern digital dollar.

The Early Days: “Not Worth a Continental”

Before the United States had its own currency, the American colonies relied on a hodgepodge of foreign coins, commodity money (such as tobacco in Virginia), and barter. The Spanish silver dollar (pieces of eight) was the most widely used coin, giving rise to the U.S. dollar’s eventual design.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress issued paper money called Continentals to fund the fight against Britain. These notes, not backed by gold or silver, quickly lost value due to rampant inflation and British counterfeiting. By the war’s end, they were nearly worthless, giving rise to the phrase, “Not worth a Continental.” This early failure demonstrated the need for a stable, trusted national currency.

The Birth of the U.S. Dollar and the Coinage Act of 1792

After independence, the U.S. Constitution (ratified in 1789) granted Congress the power “to coin Money, regulate the Value thereof.” This led to the Coinage Act of 1792, which established the U.S. Mint and defined the dollar as the official unit of currency, based on a bimetallic standard—both gold and silver. The first U.S. coins—gold eagles, silver dollars, and copper cents—circulated alongside foreign coins, which remained legal tender until 1857.

Paper money, however, took longer to standardize. In the early 19th century, state-chartered banks issued their own banknotes, each with different designs, values, and reliability. These notes were redeemable in gold or silver but varied widely in credibility, leading to counterfeiting and economic instability.

Civil War Crisis: The Birth of the Greenback (1862-1879)

The Civil War forced the federal government to find new ways to finance itself. In 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, introducing the first widely used federal paper money: United States Notes, or “greenbacks.” These were not backed by gold or silver but were declared legal tender for all debts except tariffs and interest on federal bonds. Their value fluctuated wildly, as they could not be redeemed for gold or silver until the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875, which restored convertibility in 1879.

The Gold Standard Era (1879–1933)

After the Civil War, the U.S. economy stabilized under the gold standard, officially codified by the Gold Standard Act of 1900. This system tied the dollar to a fixed weight of gold ($20.67 per ounce), meaning paper money could be exchanged for physical gold.

However, while this promoted monetary stability, it restricted the money supply, making it harder to respond to economic crises. The limitations of the gold standard became apparent in bank panics, including the Panic of 1907, which nearly collapsed the U.S. financial system.

The Federal Reserve and the Rise of Central Banking (1913–1933)

The Panic of 1907 exposed major weaknesses in the banking system, leading to the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. The Fed introduced Federal Reserve Notes, which remain the U.S.’s primary form of paper currency today. Initially, these notes were backed by 40% gold and redeemable on demand.

However, the Great Depression (1929–1939) triggered widespread bank failures and gold hoarding, leading President Franklin D. Roosevelt to take radical action in 1933. He banned private gold ownership (except for jewelry) and ended gold redemption for paper currency. In 1934, the Gold Reserve Act further devalued the dollar, raising gold’s price to $35 per ounce. This shifted the U.S. to a modified gold standard, where only foreign governments could redeem dollars for gold.

Bretton Woods and the U.S. Dollar’s Global Dominance (1944–1971)

After World War II, the U.S. led the creation of the Bretton Woods system, which made the dollar the world’s primary reserve currency. Under this system:

• Foreign currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar.

• The U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce.

This arrangement solidified the dollar’s dominance in global trade and finance. However, by the 1960s, excessive government spending on Vietnam War costs, social programs, and trade deficits caused inflation and led other nations to demand gold in exchange for dollars. The system came under severe strain.

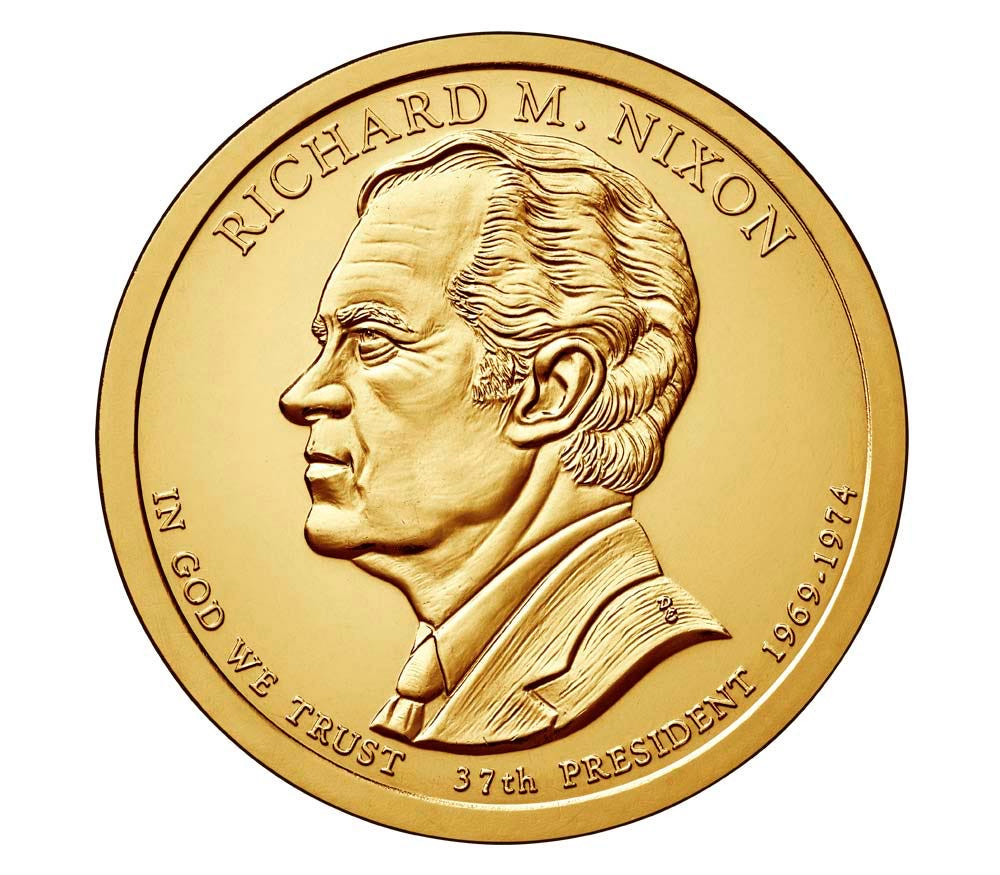

The Nixon Shock (1971): The End of the Gold Standard

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon announced the “Nixon Shock”, ending dollar convertibility into gold. The Bretton Woods system collapsed, and currencies floated against each other in the open market. The U.S. dollar became pure fiat money, meaning its value was based solely on trust in the U.S. government and economy rather than a tangible commodity like gold.

This shift to a fiat currency gave the Federal Reserve more control over monetary policy, allowing it to expand or contract the money supply as needed to manage inflation and economic cycles.

The Modern U.S. Dollar: What Drives Its Value?

Since 1971, the U.S. dollar’s strength has depended on several key factors:

1. Trust and Stability – The U.S. economy’s size, military power, and political stability underpin global confidence in the dollar.

2. Monetary Policy – The Federal Reserve controls interest rates and money supply, influencing inflation, employment, and economic growth.

3. The Petrodollar System – Since the 1970s, OPEC nations have priced oil in U.S. dollars, creating global demand for dollars as the world’s energy currency.

4. Debt and Deficits – The U.S. borrows heavily to finance deficits, making the dollar’s value tied to government creditworthiness.

5. Digital Evolution – The rise of digital payments, cryptocurrencies, and Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) concepts is reshaping how money is used, though Federal Reserve Notes remain dominant.

From Metal to Faith

The U.S. dollar has transformed from hard commodity money (gold and silver coins) to paper backed by precious metals, to a fiat currency based on trust. Each transition was driven by necessity—war, economic crises, or global shifts.

Today, the dollar remains the world’s primary reserve currency, but its future faces new challenges: rising national debt, inflation, and the rise of digital finance. Whether the dollar will remain the dominant global currency or give way to a new financial paradigm remains an open question.

One thing is certain: money is not just about metal, paper, or digits on a screen—it’s about trust, power, and the economic forces that shape our world.

Gold vs. Dollars: The Truth About the Value of Money

Once you stop thinking in terms of dollars, you quickly realize how governments and bankers have systematically undermined your purchasing power.

Let’s consider an eye-opening example: In 1929, a troy ounce of gold was worth $20. A 10-kilogram bar of gold (321.5 ounces) would cost $6,430. Today, in 2025, an ounce of gold is valued at $3,165.70, meaning that same 10kg bar would cost $1,017,772.55.. On the surface, it might seem like gold has skyrocketed in value. But that’s not the real story.

The True Value Comparison: Gold and Homes

In 1929, the average price of a home in the United States was $4,902. Back then, a 10kg bar of gold could buy you a nice house with some cash left over. Fast forward to today, where the average U.S. home price is $412,095. Remarkably, 10kg of gold still buys you a nice house, with plenty of room to spare.

What’s the constant here? Gold. What’s changed? The purchasing power of the dollar.

The Decline of the Dollar

Since 1929, the dollar has lost a staggering 99.14% of its purchasing power. This loss isn’t due to natural market forces; it’s the result of deliberate monetary policies—printing more money and expanding the currency supply to meet the demands of governments and financial institutions. While wages, housing prices, and basic goods seem to have “gone up” over time, what’s actually happening is the dollar is worth far less than it used to be.

To put it in perspective:

• In 1929, $1 could buy five loaves of bread. Today, that same dollar might not even cover a single loaf.

• A new car in 1929 cost $600. Today, even an economy car will run you close to $30,000.

It’s not that goods are more expensive—it’s that the dollars used to buy them have been devalued.

Gold: The Standard of Stability

Unlike the dollar, gold has maintained its value over centuries. Whether it’s 1929 or 2025, a kilogram of gold translates into tangible, stable purchasing power. It’s not subject to the whims of central banks or inflationary policies. Instead, it serves as a benchmark, exposing the erosion of fiat currencies like the dollar.

What Can We Learn?

The real takeaway isn’t about investing in gold versus dollars; it’s about understanding the hidden mechanics of inflation and monetary policy. When governments print more money, they dilute the value of every dollar already in circulation. This makes your savings, your paycheck, and your retirement fund worth less over time. Gold, by contrast, remains a hedge against this systematic devaluation.

The next time someone says, “Prices are going up,” challenge the premise. It’s not that prices are rising—it’s that the dollar is shrinking. Understanding this distinction is the first step toward financial literacy and empowerment in a system that thrives on obscuring the truth.

Money by Pink Floyd (1973)

Money

Get away

You get a good job with more pay and you're okay

Money

It's a gas

Grab that cash with both hands and make a stash

New car, caviar, four star, daydream

Think I'll buy me a football team

Money

Get back

I'm alright, Jack, keep your hands off of my stack

Money

It's a hit

Don't give me that do goody good bullshit

I'm in the high-fidelity first-class traveling section

And I think I need a Lear jet

Money

It's a crime

Share it fairly, but don't take a slice of my pie

Money

So they say

Is the root of all evil today

But if you ask for a rise

It's no surprise that they're giving none away

Away, away, away

Away, away, away